Balancing the Bench and Motherhood: Women, Work-Life Balance, and Gender Inclusion in Nigeria’s Judiciary

By Joy Azu, Intern IAWJ

The Nigerian judiciary stands as a symbol of justice, integrity, and the rule of law. Yet behind the dignified courtrooms and the authority of the bench lies a quieter narrative—one of women who must constantly negotiate between their professional roles and the expectations society places upon them. On 13th of November 2025, the National Association of Women Judges (NAWJ-Nigeria), in collaboration with the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ), convened a landmark webinar on “Enhancing Work-life balance and accessibility in a court setting”.

Gathering accomplished judges, scholars, and court administrators, the webinar shed light on both the systemic challenges faced by women in the judiciary and the inspiring resilience of those who continue to break new ground. Through personal stories, institutional case studies, and policy recommendations, the sessions highlighted how the judiciary can become more inclusive—and what remains to be done.

Wisdom from the Bench: Navigating Work-Life Balance

The opening session, delivered by Hon. Justice Adenike Josephine Coker (JP) and Hon. Justice Josephine Oyefeso, explored the realities of blending judicial duty with motherhood. Justice Coker addressed the long-held notion that pregnancy can hinder professional performance, especially for newly appointed judges:

“Pregnancy is not a disability, but it can be perceived as a hurdle to high productivity, especially if you’re just starting your childbearing,” she noted.

She stressed the importance of strong support structures—both familial and professional—so women are not overwhelmed by the dual pressures of early career expectations and motherhood.

Justice Oyefeso echoed this sentiment, drawing attention to the lack of formal structures to support young female judicial officers. She described what she called the current “do-it-yourself system” faced by many women:

“Thankfully, we all have our chambers. You can bring your baby in with your nanny, or leave them with your parents. But whoever is coming onto the bench must realize it’s a do-it-yourself system.”

Both judges emphasized personal well-being as essential to judicial excellence. Hon. Justice Oyefeso reminded participants to prioritize self-care, using a vivid metaphor:

“Put on your face mask before helping someone else.”

Her message—clear and compassionate—resonated strongly throughout the session.

A Creche in Court: Institutional Support in Action

The second session showcased a promising initiative for institutional support: the revival of a creche within the Abia State High Court. The presentation, prepared by the Honorable Chief Judge of Abia State, Justice Lilian Abai, was delivered on her behalf by Administrative Judge Hon. Justice Chinwe, illustrating how such institutional initiatives can transform the daily realities of working mothers.”

Justice Chinwe explained how the project began:

“When the Chief Judge came into office, she discovered that the creche was abandoned. She took up the challenge to restore it,” she said. With the assistance of Her Excellency the wife to the governor of Abia State, Mrs. Priscilla Chidinma Otti, the creche was renovated and formally launched during the 2025 World Breastfeeding Week.

The impact was immediate and tangible. Two young mothers on the court’s staff shared how the proximity of a creche completely reshaped their work performance. One who had once balanced childcare with demanding chamber duties reported newfound efficiency in assisting with court proceedings and case management. The other, previously overwhelmed by record-keeping responsibilities, described a remarkable improvement in her ability to meet—and even surpass—work; Honorable Justice Chinwe summarized it succinctly:

“The proximity of the creche allows mothers to concentrate better on their work without the distraction of managing a child at the workplace. It gives them peace of mind, enhances productivity, and opens avenues for career growth.”

More than just a convenience, the creche symbolizes a deeper cultural shift: a recognition that motherhood and professional ambition need not exist in conflict. It stands as an example of how thoughtful institutional policies can directly contribute to a healthier, more equitable judiciary.

The Need for Gender-Inclusive Policy

The third session, led by Chief Registrar Nkechi Yvonne Usani of the Cross River State Customary Court of Appeal, confronted structural barriers that limit women’s advancement in the judiciary. Her presentation highlighted the ways marital status, cultural biases, and outdated administrative practices often disadvantage women—regardless of their qualifications or years of service.

Drawing from personal experience, she described a persistent dilemma:

“I got married to a proud Yakurr man from Cross River State. For my career progression, where exactly do I come from? My birth state or my marital state?”

Her story underscored the uneven expectations placed on women. While a man’s marital status rarely affects his judicial career, a woman’s marital status can raise questions about her state of origin or where she ‘comes from,’(is she from her birth state or her husband’s state) which can unfairly influence decisions about postings or promotions.

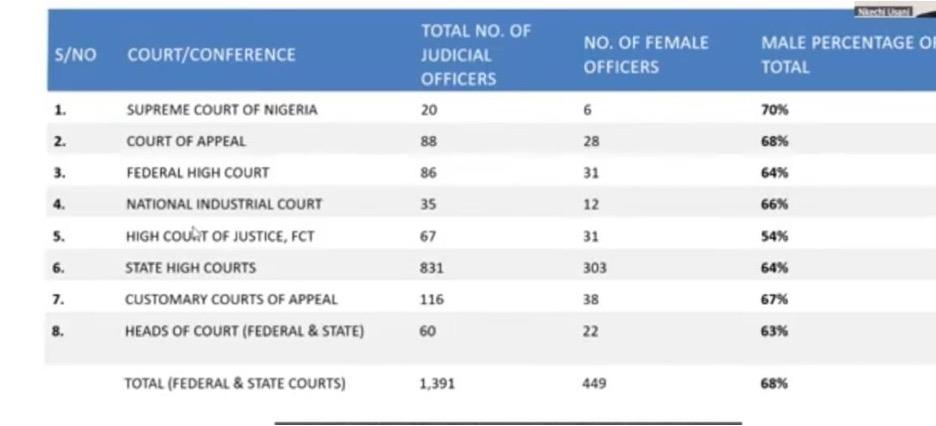

She also presented sobering statistics:

Men constitute 70% of the Supreme Court, 68% of the Court of Appeal, 64% of the Federal High Court, and in many state high courts, men hold more than 60% of judicial positions.

In her own court—the Customary Court of Appeal—80% of judicial officers are male.

She argued that gender parity is both a practical need and a constitutional obligation. She called for reforms aligned with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and CEDAW, urging judicial institutions to eliminate practices that penalize women for marriage, childbirth, or cultural expectations.

She quoted a powerful message from Amie Lewis, IAWJ WILIL Senior Program Officerl:

“Achieving gender parity in judicial leadership is not just about fairness. It strengthens public trust and creates a judiciary that is more inclusive, responsive, and representative of the society it serves.”

A Judiciary that Reflects Society

In their closing remarks, Justice Mulibat Oshodi and Amie Lewis emphasized that a judiciary’s strength lies in its ability to support all its members—including those balancing caregiving responsibilities.

Amie Lewis who is the senior programs officer of the IAWJ observed:

“When courts accommodate the realities of caregiving and accessibility, talent can thrive, career satisfaction is enhanced, inclusivity becomes a lived reality.”

The webinar pointed toward practical reforms: on-site childcare facilities, breastfeeding and nursing rooms, flexible scheduling where possible, and transparent, gender-neutral recruitment and promotion standards. These are not luxuries—they are necessary steps toward a judiciary capable of drawing from the full range of talent Nigeria has to offer.

Conclusion: A Path Forward

The stories and insights shared during the webinar form more than a discussion—they form a roadmap. They illustrate what a gender-inclusive judiciary can look like: one where women do not have to choose between motherhood and professional excellence, where policy reflects the reality of modern families, and where justice is not only practiced but embodied within the institution itself.

A judiciary committed to fairness must extend that fairness inward. And as this webinar showed, Nigeria is already taking promising steps toward that future—creche by creche, policy by policy, voice by voice.

Joy Azu is a final year law student, University of Calabar, Calabar . She is currently an intern with the IAWJ.